PATAGONIAN CHRONICLES

DIARY OF MY VERTICAL CHALLENGES AGAINST TIME

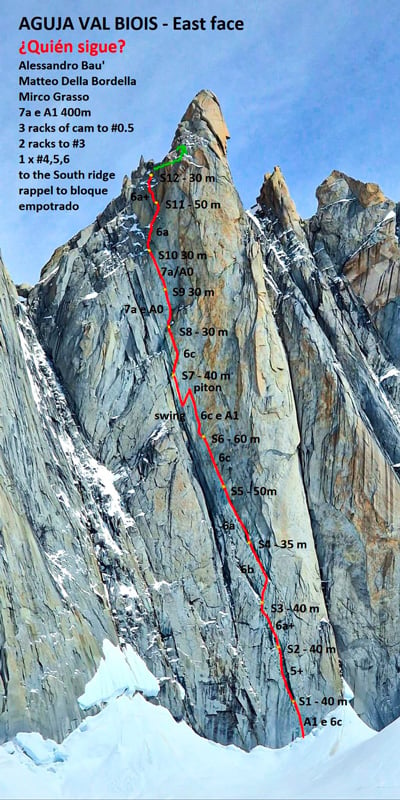

by Mirco Grasso

In December 2024, Mirco Grasso returns to El Chaltén to tackle routes cutting across the most iconic towers in mountaineering. As the weeks pass, his debut with climbing partner Matteo Della Bordella transforms into a succession of adventures and encounters, including one that will lead them to close the circle on a project left incomplete for almost three decades, on the west face of Cerro Piergiorgio.

CHAPTER 1 – THE RULES OF THE GAM

It’s Christmas Day, it’s 9 p.m., and there’s still a lot of light in the sky. Finally, after a journey lasting dozens of hours, I find myself once again in the magical village of El Chaltén.

There’s not a cloud in the sky, and the Fitz Roy and Cerro Torre ranges are illuminated by the last blazes of the midsummer sky. A sight you never get used to!

It’s been five years since my last expedition in Patagonia. Accessing the mountain range’s mixed rock and ice walls requires long approaches, and a foot injury forced me to reconsider my vertical plans for the following seasons. My recovery has proceeded smoothly over the past two years, and the persuasive powers of my friend the champion Alessandro Baù did the rest. For several months, Ale and I have been planning to open a new route on Fitz Roy: a dream as impossible as it is tempting. So, here I am again.

Yes, climbing these legendary mountains. A playground unlike any other in the world. I’d read about it in the manuals of those who made history in the Andes, and I’d experienced it firsthand during my two previous trips. First and foremost, it’s essential to always have a plan B. Rule No. 1: Physicality goes hand in hand with flexibility. To try to achieve something in these mountains, it’s important to know how to adapt to the weather and balance your goals based on the days — sometimes just hours — you have available.

In the last 20 years, the style of climbing in Patagonia has changed drastically, thanks to the development of El Chaltén (from a modest hamlet to a modest village of a thousand inhabitants) and the tools that make weather forecasts increasingly accurate. Mountaineers of the generation before mine camped near the face they’d decided to target. Barometer in hand, they stayed in their tents waiting for clear skies to make a summit attempt. The room for maneuver was limited.

Today’s mountaineers, in contrast, constantly monitor the forecast, and as soon as they identify a window of good weather, every team prepares its plan of attack. The approach usually precedes the start of the window of good weather. In the afternoon, you camp at the foot of the mountain you intend to climb, and once the climb is complete, you return to town when the weather worsens again. This way, you can make the most of every available hour and be flexible about your goal based on the duration of the good weather. The only unpredictable aspect is the condition of the face you’re attempting to climb. After a few weeks of precipitation, the rock, especially where less exposed to the sun, may be damp and covered in a thin layer of ice in some areas. An unpleasant surprise that can significantly reduce your chances of reaching the summit.

Another unwritten imperative of the game in Argentina is the need to be ready and always motivated. Rule No. 2: The anticipation of pleasure is pleasure itself. Being confined to El Chaltén for weeks on end, unable to climb, can be frustrating — which is why it’s important to learn to manage the waiting.

My daily recipe for surviving the restlessness that consumes me is to work in the morning, do a quick bouldering or crag session in the afternoon, and share anecdotes, impressions, and dreams with other climbers who are chasing the big prize rather than just beginning.

This brings us to the last point, which in my case is perhaps the most important one. Rule No. 3: Choose your team carefully. The team Matteo Della Bordella and I initially created perfectly balances all the ingredients needed to dream big. Teo is a veteran of these mountains, with 14 expeditions under his belt and as many first ascents or repeats. Although we’d never climbed together, Matteo and I had developed a connection ever since I learned he would be arriving in El Chaltén a few weeks after me. Beyond our approach to the wall, we share a climbing style and the mindset that we apply to tackling these mountains.

So, after having spent the last few days obsessively leafing through the guidebook with all the possible routes and filling our backpacks with gear and clothing, we set off toward the baptism of fire that awaits us.

CHAPTER 2 – THE FIRST IS GOOD (AND THE SECOND

We choose the Potter-Davis route, which runs perpendicular to the east face of Aguja Poincenot. A beautiful crack climb, it’s now a classic route, despite only having been opened in 2001. After six hours of hiking, we reach Passo Superior and pitch our tents a couple of hours from the face. Everything goes smoothly.

The next day, we attack the route without hesitation. The momentary lull in the wind has brought clouds back to the sky, and the morning sun allows us to enjoy the first moves as we had hoped. Climbing this staggeringly vertical granite, roped up with one of the world’s best climbers, is a double learning experience for me.

After the first pitches, the route becomes more exposed on the sharp ridge facing Fitz Roy. Right at that point, a cold wind picks up from the west, making me wonder if we should stop, but a glance from Matteo is enough to instantly dismiss the idea. Despite our freezing hands, we still manage to advance on the following, fairly challenging pitches, reaching the next-to-last pitch, a 7a. A pitch as fun as it is awe-inspiring: after squeezing through a very narrow passage, we emerge onto a double boulder that we literally have to straddle, given the impossibility of fitting both legs through. These are the kinds of unique formations that you can only find here.

After we reach the final ridge, 50 meters from the small pyramid of the summit, the gusts become unbearable. We decide to rappel down early, still satisfied to have gotten our hands one of the most iconic lines in the Fitz Roy group. Within a few hours, we’re back at headquarters, and we spend the next day recovering from the exertions of our debut as a team.

Once we’ve regained our strength, there’s no time to waste. After sampling the appetizer with Potter-Davis, we’re starting to crave a full meal. Besides, our time for climbing together is running out. In a few weeks, Matteo will lead the new CAI (Club Alpino Italiano) Eagle Team project, aiming to open a new route on Piergiorgio with a group of promising young talents of Italian mountaineering. Fortunately, the weather is on our side: in a few days, another favorable window of a couple of days should open up.

CHAPTER 3 – A BITTER TASTE IN THE MOUTH

With the new period of unstable weather, the usual routine resumes at Lo De Trivi, the small blue-and-white hostel where I’m staying — which is more like a typical Greenlandic house than the buildings usually found in small Argentine towns.

After a couple of weeks, a one-day window opens, albeit with overcast skies. The ice that formed during the winter should still be in good condition, but there’s not enough time to plot out a concrete plan for the new route on Fitz Roy. In Patagonia, maybe more than anywhere else in the world, you have to learn to minimize frustration about the limited time available. This is now my third expedition here, and I feel like I’ve learned to live with the risk of returning home without even having had the chance to attempt the main objective.

On this third ascent, the cards will again be reshuffled. Matteo is out, busy with the Eagle Team, as is Alessandro, who decides to climb with his very strong wife, Claudia. Francesco Ratti is in. Fra is an incredible mountain guide and climber who has made history on the Matterhorn, his home turf, as well as leaving his mark around the world. In 2023, he established “Wake Up” on Aguja Guillaumet after a 32-hour push. A true mountain professional with a body that’s a machine.

We decide to take advantage of the overcast sky to climb an ice line. The route in question is called “Exocet,” on Aguja Standhardt, a must for every ice climber.

After the long approach to Niponino, our camp near the Torre group, we set our alarm for 2 a.m., and in a few hours we’re already at the attack point of the route, which involves skirting the east face, climbing the long icy couloir for almost 300 meters. After that, another 250 meters of mixed climbing toward the summit’s ice mushroom.

We begin climbing the first pitches along the sharp crest, surrounded by a chilling wind. After a few hours, the clouds seem to thin out, so we skirt the Aguja Standhardt on the east face, staying sheltered from the wind. The state of the mountain, which had been perfect until now, changes drastically. The temperature soars and the sun melts the snow that had remained encrusted above us. We haven’t yet reached the final couloir, but our expectations are quite low.

Just a few steps from the last ice wall, we stop to consider the feasibility of the climb. The ice couloir has now become a waterfall. At this point, we need to remain clear-headed. The euphoria of the climb is not proportionate to the risk we might run by venturing into this water. The cost is too high, and we opt for the only sensible decision. We descend.

At the base of the wall, we meet another team that had started the route a little over two hours before us and managed to complete the ascent.

Our disappointment is compounded by the awareness that if we had started a couple of hours earlier, things would have gone differently. And here I thought I’d amassed enough experience already!

CHAPTER 4 – CINCO GRINGOS, TREINTA AÑOS, UNA LÍNEA

We go back to the hostel with our tails between our legs, empty-handed. At that moment, the regret at having lost the first battle against time was undeniable. But to be honest, only a few weeks after returning home from the expedition, the realization that we had attempted another aesthetically stunning route, in one of the most challenging corners of the planet, gained the upper hand.

The next three weeks of constant rain only put me further on edge. As soon as I wake up, I immediately check the forecast, hoping for a good window of opportunity — even if only for a few hours — on the horizon. Some friends have chosen less-demanding routes to keep their motivation high, while others have opted for an early return. Meanwhile, I’ve been in bed for a week with the flu, and my fitness is suffering. It’s the most challenging moment of this adventure, but I’ve learned that things can change, even if not as quickly as elsewhere.

In mid-February, the sky clears more or less, with a strong wind that doesn’t compensate for the disastrous conditions caused by the previous month’s rainfall. Despite the clear risk of not completing anything at all, I can’t deny myself the slim chance of having one last dance on these granite walls.

Alessandro and Francesco are returning to Italy as scheduled. My plan for mid-February was to find someone to climb with, and the guys from Eagle Team were the ones I had in mind. Once again, it was a chance event that gave me a choice. In an ironic twist, two of the guys from Matteo Della Bordella and Dario Eynard’s team had gotten injured. At 21, Dario had already completed several solo ascents, including the first winter ascent of the north face of Presolana. Now 23, he too has earned the opportunity to share the rope with Matteo.

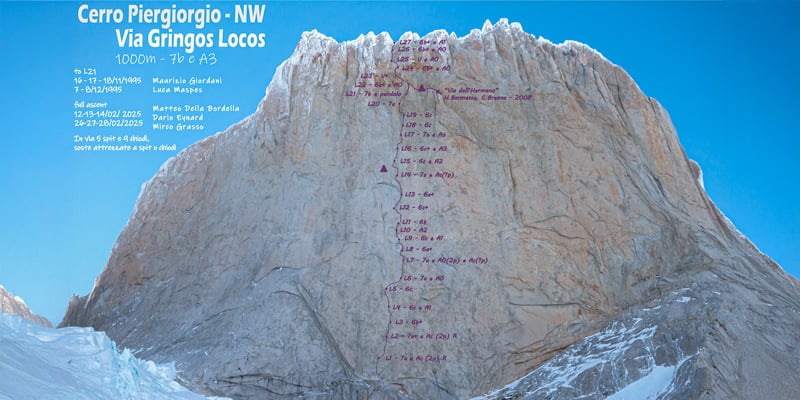

The goal is to complete a route that was started and almost finished 30 years ago by two great mountaineers, Maurizio Giordani and Luca Maspes. A line that cuts across the center of Cerro Piergiorgio, a wall as smooth as a blackboard, almost 1,000 meters high.

I’d already tackled Piergiorgio in 2018, together with some other expert climbers, but the impossible conditions prevented us from advancing beyond the very first pitches.

When Teo suggests that I join them, I hesitate a bit, considering the daunting nature of that mountain, its smooth face, and the risk of giving up a more achievable objective — because my time in Patagonia is running out.

A project this ambitious requires working in blocks during the short windows of good weather, crossing your fingers and hoping to be both capable and lucky. I take Matteo’s call as a sign of fate. From spectator to main character, on my nemesis, together with two champions. I don’t think about it for long.

As we wait for the window, we have a few days to prepare and decide on our plan of attack: try to get as high as possible during the first interval, placing fixed ropes, and climb back up to that point during the second interval, trying to complete the route.

We reach the base of Piergiorgio after a long approach of about 10 hours, and Matteo starts. His confidence helps Dario and me shake off the awe this face inspires. I take the second pitch, which may be one of the most challenging in the initial push due to a smooth, unprotected 10-meter section preceding the only bolt, which has been there for over 30 years.

Over the next few days, we each complete two pitches, alternating free climbing — with difficulties up to about 7a+ — and aid climbing, which requires great mental stamina. When the sun sets, we return to base camp to bivouac.

Proceeding in this way, we manage to complete 14 pitches, placing all the ropes we had with us, as we’d planned. We’re halfway there, but we’re forced to return to El Chaltén because storms are approaching. In about seven hours, we’re back at Lago Eléctrico, where the taxi to El Chaltén picks us up.

We’ve decided to go all in. If a window of good weather doesn’t open up in the next two weeks, we’ll have to go back in the storm (or rain) to collect our gear and say goodbye to Piergiorgio from up close. That would be a cruel joke.

Our patience is rewarded once again. We have just three days left to complete the route before our flight home. Seventy-two hours to complete the adventure started in 1995 by Maurizio and Luca. After five days on the wall, with the equipment of that time, they had opened nearly 800 meters of the total 1,000 meters — 21 pitches, to be precise. The project remained dormant for 30 years, perhaps due to the difficulty of accessing the wall, or the lack of a window with several days of good weather. Or perhaps due to the fear this rock shield inspires.

With the window approaching, Maurizio catches a flight from Italy and arrives in El Chaltén. With his usual thoughtfulness, he gives us his blessing. Another good omen for the alignment of influences.

In the days leading up to the big event, I manage to keep up my training. I climb pitches up to 8b and boulders up to 7c in spots near the village. The tension is palpable, and we all have serious expressions on our faces because we know that this is truly the last climb before the summer ends.

We go over the plan one last time: day 1, arrive at the base; day 2, reclimb the completed pitches and start on the next ones; day 3, finish the climb and reach the summit; day 4, backup if we’re slower than expected, and descend off the face; day 5, return to El Chaltén.

We set off for the last time. As we walk, the sight of the other snow-covered walls gives us serious doubts about whether the ropes we’ve fixed will have held, as well as how climbable the rock is. Finally, shortly after our arrival, the sun peeks out, melting the snow and drying the wall. Through our binoculars, we see that the ropes are still in place. We’re ready!

We reclimb the first part faster than expected, and Dario puts up another pitch. On the next one, though, we’re forced to stop because the wind is very strong, and a waterfall has formed above us from the melted snow. But we find a small terrace a bit below, where we secure the portaledge and take shelter. Meanwhile, the satellite weather update arrives. Bad news: very strong wind is forecast for the fifth day. No backup day.

We decide to try it anyway. Despite the bitter cold, the sun is still shining and the wind seems quiet at the moment. Dario sets off, literally dancing on the cliff, and completes the pitch that looked quite difficult from below. This is probably the turning point that allows us to advance. Matteo strings together four pitches in no time, and then I take over and surpass the highest point reached by Maurizio and Luca.

By this point it’s getting dark, but the worsening forecast leaves us no choice. We can’t stop — we’re not descending until we reach the summit!

I continue, giving it my all. I complete two more pitches by willpower alone — my energy has been used up for hours. I pass the ball to Dario, whose task it is to finish the last three pitches and reach the summit ridge. He climbs with great confidence and reaches the end of the 27th pitch. Teo and I join him. It’s 3 a.m. and we don’t even have the energy to scream, but we’re at the summit of Piergiorgio!

At that moment, we don’t realize that getting down will be just as complicated. We descend a bit toward a terrace where we set up the portaledge and can melt snow for water. After just three hours of sleep, we’re awakened by the snowfall that’s about to envelop us. We pack up our gear and descend at full speed.

It’s 3 p.m. when we finally reach the base, with our faces relaxed at last.

This time we don’t have to argue about the route’s name. “Gringos Locos” was the name Maurizio and Luca chose, inspired by the nickname the manager of the Piedra del Fraile hostel had given them, meaning “crazy foreigners.” It’s a story that has lasted almost 30 years and now unites us on a beautiful thousand-meter route. A fitting finale to more than two crazy months of Patagonian chronicles.